Do you remember your first day in New York?

It was in 1992 or 1993. I came on a trip with other students from my art school. We were staying at a hotel in Washington Square. I immediately felt that this is not Europe, that the US is something completely different. At that time, we didn’t have the Internet so when you were coming to a new place you actually were seeing many things for the first time.

It must have been a shock. Iceland, your motherland, is mostly about nature and vast space.

In Iceland, we are isolated. We have no neighbours, there is just the water around. Nevertheless, many Icelanders come back to live on the island because it’s a very special country – the minimalistic landscape, the small population… But, personally, I had to escape Iceland. I heard it is common for people who were born on islands. In New York, I felt that I can re-invent myself.

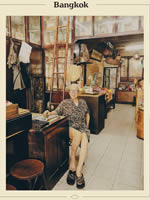

Images by Elisabet Davids

Did you re-invent yourself as Shoplifter? How did you come by your nickname?

It’s really ridiculous. In my first month of moving to New York, someone misheard my name and mispronounced it. I didn’t give up Hrafnhildur Arnardóttir, but Shoplifter was just easier to pronounce. I decided to use it also in order to get to the core of who I am in New York, without all the baggage of my pastor upbringing in Iceland.

A young, beginner artist in New York – it must have been a real survival.

In Iceland, I finished my bachelor in painting so in the States I had to step outside of the rigid framework of paint, easel, and canvas. I was mixing domains, I didn’t want to be labelled. I applied for the School of Visual Arts where I knew I would be able to use whatever media I wanted. I was given a huge freedom. You know that I deliberately didn’t even bring any art from Iceland nor any painting tools. I really wanted to start from the scratch.

You didn’t have a portfolio?

No! I applied and I was accepted. In Iceland we had an education loan system, so the government was covering the tuition and living expenses if the master programme of your choice wasn’t available in the country. It covered my two years of studies. I’m still paying off these loans, but they aren’t very high. I was extremely lucky that I was having the help of a rich Scandinavian country. Many students were stressed out of their minds. They were under the pressure of running out of money, ending up in the street and being homeless for the rest of their lives.

You were lucky but your works are also very impressive. You often work with hair, how did you start using it as a medium?

In my art, there’s a lot of fantasy and cartoons. I am inspired by the abundance of pop culture. I am a shopaholic, I like collecting things. I have a fetish for colours, textures, and shapes and bizarre objects that are mass-produced but make no sense. The banana cutter for example – it is both abstract and absurd. Initially, I kept finding things and covered them in glue and put them together creating worthless garbage, almost like nothingness. I was using tape, vaseline, fishing lines, transparent materials and industrial glue. It was not about the message that the work of art carries. I just perceived myself more as a craftsman than a painter. I started using hair because I believe that even a single hair can express the drawing on a paper. A hair is a line, and when I am using it, it feels like I am collaborating with the material, and this material is collaborating with me. I do not only create I surrender to it.

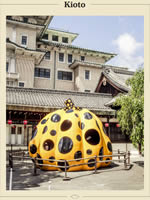

Nervescape V by Hrafnhildur Arnardottir / Shoplifter at Qagoma, Brisbane, Australia, November 2016. Images by Natasha Harth

Visiting your studio, I had an impression that you allow your works to mature.

Because my projects are more than just hair sculptures. They are the final effect of a process, which is far more complicated than it seems. People had been using horse hair for years but in a limited amount. I have always been fascinated with the abundance, the widespread availability and the monstrosity of mass production. I wanted to confront the viewer with too much of something. I’m not saying that bigger is better, especially when it comes to art, but this is how I am affecting the viewers. But I also like to create microscopic, colourful, 3-dimensional drawings with different colours of hair melted together. I can work with a material that seems very scattered and disconnected from individual things but once you start looking at it, there is a complete consistency.

I can see this consistency in the way you style yourself, your clothes and accessories. You are very much about fashion.

Yes. Especially pop fashion. You know I am 52, but I had my first grey hair as a twenty-year-old. I have never really cared about dressing according to age or my standing. I’m a textile artist by accident because I use fabrics, I work with synthetic and human hair.

How do you take care of your artistic development?

20 years ago, I had this vision that reminds of “Alice in Wonderland”. I felt like I’m coming through this dark, round room and there were just doors. I was allowed to go into every room, neither was locked. It represented to me the guarantee that nothing will limit my creativity. So I am developing by questioning prejudices about what an artist should or shouldn’t be and not accepting limitations of the so-called fine art world and its monopoly over other art. My art is just more expensive because it’s not mass-produced. It is not practical, it’s like poetry but it speaks to the intellectual and emotional life of people. It’s a life philosophy to be an artist – it’s a career choice. You have to have a lot of hope and faith and optimism to sustain years of working without people recognising what you do. I think that what helped me is that I am a very social person and I used to party like crazy and making performances.

You collaborated with & Other Stories, you designed a special, limited collection for them.

& Other Stories approached me because of my art. They had no idea that I used to do fashion before. The challenge was to find a way to translate my artistic point of view into the collection, make something more than just clothes with prints of my art. However, I also had to remember that it is about fashion. It had to be coherent within itself. I trusted my intuition.

Images by Elisabet Davids

How do you survive in the art market in New York?

I don’t quite survive (laughs)! I am like a little, colourful turtle.

Artnet listed you as one of the 50 most exciting artists from Europe!

It’s because I come from Europe (laughs)! I am lucky to be able to play in both teams: the European and the American. First of all, I am from Iceland but I have been living in the States for 25 years. Before that my creative, intellectual, adult life lasted only 8 years. It was only here that I truly developed my art. You could say that Iceland is like a skeleton and New York is like muscles.

The rest of the interview in the new issue of the USTA Magazine, available here

Interview by: Agata Endo Nowicka

Nervescape V by Hrafnhildur Arnardottir / Shoplifter at Qagoma, Brisbane, Australia, November 2016. Images by Natasha Harth

LIKE A LITTLE COLOURFUL TURTLE