Beaujolais nouveau was born in the 1950s, using the traditional St Martin’s Day date, which in many European countries is associated with the end of the wine year and the release of ‘new wine’. Beaujolais created a brand of its own from this tradition. Beaujolais nouveau now accounts for more than 20% of the region’s vineyard production. Each year, more than 160,000 hectolitres of this young wine are drunk worldwide.

The unleashed marketing machine has also brought consumer traps, it happens that the wine under this banner is not necessarily quality. It may have been created in a hurry, rushed by the vision of making money. I went to France, to the region where the most famous young wine comes from. To the vineyards south of Mâcon, and north of the gastronomic capital of France, Lyon, to see if it had more to offer than just a drinkable few weeks after bottling?

I gathered a base of contacts while working at the French bistro Levan in London. I asked exhibitors at French wine fairs and key suppliers of cheese and charcuterie in London about the best contemporary wine producers in Beaujolais. And that’s how my itinerary was created.

I found out that these dozen or so wine villages growing wine from the local gamay varietal are a mecca for organic wines. An unofficial but vital centre for promoting the production of wines without outside interference or pesticides. Before it was fashionable to do so. They are characterised by a delicate red colour – typical of what is popular in the region – dry carbonic fermentation. This technique involves uncrushed, whole grapes fermenting without air in a closed vat. This stage is also known as maceration.

When pesticides ‘protected’ plantations and crops across Europe from pests after the Second World War, Beaujolais wine producers agitated in the US market for a return to natural, chemical-free farming. They did not change the American market but, through an importer called Kermit Lynch, introduced organic Beaujolais wines to it.

This image success was earned by pioneers of organic wines in the region, including Marcel Lapierre, Guy Breton, Jean Foillard, Jean-Paul Thévenet, Jean – Jacques Robert and Joseph Chamonard. These iconic winemakers erected an invisible monument that is still recognised today by many young winemakers in the Beaujolais villages, believing that non-interventionist wine is the heritage of their region. In contrast, the first organic Beaujolais was produced by the winemaker in question – Marcel Lapierre – in 1984.

For it was the 1980s that saw the natural wine movement in France, which also had the backing of representatives of the scientific world. Noteworthy are the achievements of a biologist, researcher and wine expert named Jules Chauvet. He is a specialist in the role of yeast, acidity and temperature in fermentation processes and the aforementioned carbonic maceration. His pupil was Jacques Néauport, who visited more than two thousand French vineyards in seven years. Working with winemakers from Beaujolais and other wine regions, he was responsible for the creation of millions of bottles of wine without any chemical additives.

It would be wrong to point to Beaujolais as a “lonely island” in the propagation and maintenance of the organic wine tradition, while the natural wine movement, promoted throughout France, had its strong representation precisely in this region.

So I visited the Guy Breton winery, the largest of the wineries I’ve managed to get to. Each of its elegant wines is invariably made without any chemical intervention and, despite being one of the world’s most recognisable winemakers, there is no signboard or system for booking appointments. The supercilious Jess, who handles the winery’s image, has added two more important names to the list already mentioned: Yvon Métras and Jean Cloude Chanudet. While each is held in high esteem, I decided to seek out those who make up the contemporary second wave of organic Beaujolais wines.

In reviewing the list of recommendations, I ended up at the home of the four siblings who run Domaine Thillardon. Who, the day before I arrived, had thrown a big party to celebrate the pressing of the last batch of 2023 grapes. The grand outdoor celebration brought together almost 100 winemakers from the region. There was only one unwritten condition for appearing on the guest list – fidelity to the principle of producing wines by natural means. The siblings live in a house surrounded by fields of gamay bushes. The grape grows on two sides of the hill giving rise to two completely different flavours of wine. One calmer and elegant the other more mineralised and boozy. Both wonderful.

In siblings’ house, there is an old photo of my grandfather tasting Beaujolais on the wall. I had hoped that he was the forerunner of the wine tradition in the family, which would have looked good in this article, but in reality he was just a wine-drinking enthusiast. Just that and maybe that much. I won’t forget those wines or that visit. The openness of the siblings to present the results of their hard work, how we built a makeshift place to take photos of the bottles against the vines and how we tried to communicate without speaking a common language.

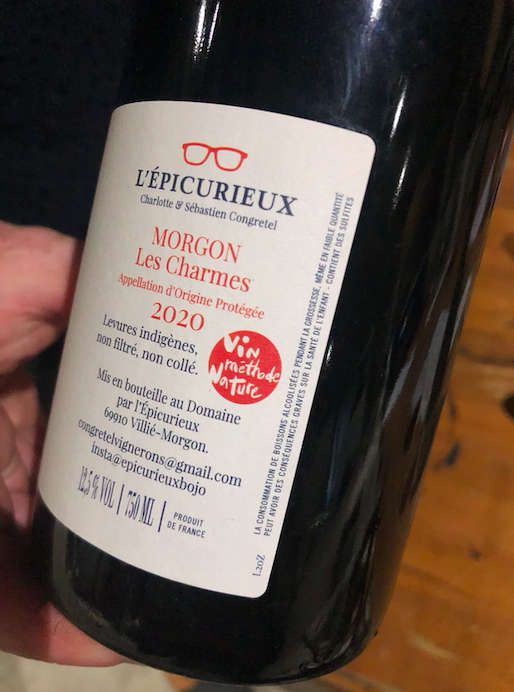

The trail marked out by a list of recommendations took me to several more extraordinary places. This is how I met Sébastien Congretel and his L’epicerieux. He treated me to his perfectly balanced, also mineral Beaujolais. Together we recognised that this wine matures like a person and has a completely different character when it is crawling, when it reaches adulthood and when it is fully ‘grown up’. It is up to the consumer to decide when to open it, but the timeline for this varietal is very dynamic. It is said that over a long period of time, it is closer in character to pinot noir.

Sébastien took over production from his talented wife Charlotte, who felt fulfilled but lonely in her work with grapes – she missed working with people. So they seamlessly took over from each other. My next host, is highly orthodox about the winemaking process. Perhaps this was taught to him by the biodynamicist Julien Sunier, from whom he took lessons. His overriding maxim is ‘no step can be contrary to nature’.

If you manage to come across his wines somewhere then you are not only very lucky, but also have the opportunity to learn about a very capacious designation, on the labels of French wines. The “Vin methode Nature” label next to the counter label is a guarantee of organic production and respect for the rights of those involved in the process, including the rights of women. The author of L’epicerieux also warns against the wrong choice of Beaujolais. Produced in the opposite trend to organic production, which, in a wave of popularity for the varietal and the region, can sell out and disappoint. According to Sébastien, one signpost of choice can be the label. Classic, but with a slight contemporary twist.

A unique label with three sardines (Les Sardines), created by the locally renowned graphic designer, sommelier and wine enthusiast Danis Pasiet, features wines that are already being made outside the Beaujolais appellation, on the border with Burgundy, the Denogent brothers’ wines. Their father, Robert pioneered the production of organic white wines in the region so when you are in Beaujolais it is therefore worth bearing in mind that fantastic white wines are also made here, already produced from the classic chardonnay varietal.

I had the opportunity to taste such at the home of brothers Antoine and Nicolas . The vineyard is guarded by a menacing-looking dog, which in practice is greedy to be stroked, and the brothers are the cuddly hosts. You can find an image of the three in the contact section of the producer’s website. The winery has a cheerful atmosphere and a great openness to sharing knowledge. Wines from the region are characterised by pronounced acidity, and the producers’ craftsmanship is to catch its peak moment at which the acidity breaks away passing into a velvety finish.

Wandering further north from Lyon, I ended up at Maison Valette, already located in the southern part of Burgundy – the pearl of the region. Although these are not Beaujolais wines, their quality is unparalleled. The owner of the vineyard, together with her husband, cultivates the philosophy of organic farming and, interestingly, due to her own love of animals, does not use horses to work in the vineyard – and this aspect, often identified with the production of organic wines – she boycotts. I’ll never forget the dusty bottle of 2014 chardonnay she opened especially for me.

After a wave of popularity, Sèlènè wanted to produce more complex and demanding wines. Such will be, among other things, the wine he is creating in memory of his late friend. With the idea of helping his family, he has taken care of the remaining vines of the exceptional gamay teinturier grape. Each of the compositions I tasted at Silvere’s was a top-notch rock concert. “Rockman” of winemaking, that’s how I will remember him, and I encourage you to look out for his wines in every latitude.

I didn’t manage to get everywhere like, for example, the Domaine Chapel vineyard, run by a pair of Americans who chose a challenging terrain to grow on, but with hard work and impressive results won sympathy and appreciation. Some visits were also far too short, such as the one to the picturesque Jean-Claude Lapalu vineyard, where today it is the granddaughter who enthusiastically recounts the slow process of pressing the grapes by natural means, which takes several hours. The lucky ones, on the other hand – myself included – have the chance to shake the hand of the ever-active Mr Lapalu at the winery.

Beaujolais more than repays the patient, and satisfies the impatient with a superb Beaujolais nouveau that can be purchased across the latitude of the world. Local gems, on the other hand, are produced by passionate winemakers in small quantities for personal use and local needs – including supplying the city of Lyon. So you might want to consider a trip to this area in autumn. You will feel “at home” here, as vineyard and home are fused parts of the wine landscape, at least in this part of the old continent.

List of Polish suppliers of the wines mentioned:

Domaine Lapierre / Winoblisko

Jean Foillard / Wolne Wina

Jean-Claude Lapalu / Free Wines

Maison Valette (Burgundy/Mâconnais) /c

Sylvère Trichard / Séléné / Natural Rascal

other recommended available in Poland:

Laurence Liatard / Rémi Dufaitre / Winemates

Jean-Paul Brun / Terres Dorées / Deliwina

Michel Guignier / The Naturalists

Thanks to Lechoslaw Olszewski, wine expert and enthusiast. Lecturer at WSET, associated with SPOT Poznań, among others.